The anticipation is building in the private, tatami-mat room at Murasaki, a restaurant in Osaka. At one end sit a handful of Japanese journalists; on the other, executives from the country’s biggest whaling company and officials from the travel industry.

In the middle, six hand-picked social influencers from Thailand, France, Russia and South Korea take their places around a hori-zataku table and wait for the first of several courses devoted to Japan’s most controversial cuisine: whale meat.

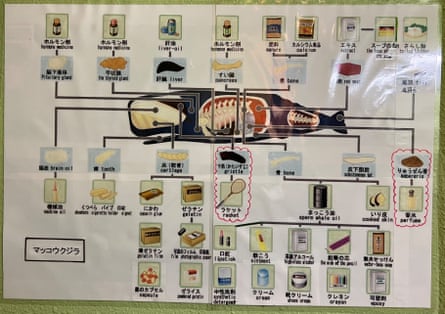

Over the next two hours they will eat dishes – simmered, grilled, deep-fried and raw as sashimi – made from the mammal’s jaw, stomach, ribs, tail, cheek and back – although it appears they have been spared another cetacean delicacy: the penis.

By the end of the banquet, their hosts hope they will take the industry’s message to their followers – that after decades of hiding in the culinary shadows, whale meat is delicious, and eating it a socially acceptable part of the tourist itinerary.

The evening began with a pep talk from Hideki Tokoro, chief executive of Kyodo Senpaku, Japan’s biggest whaling company, who claimed that hunting whales, which consume the equivalent of 4{0b5b04b8d3ad800b67772b3dcc20e35ebfd293e6e83c1a657928cfb52b561f97} of their body weight every day, helped protect the marine food chain.

“We need to control the whale population to protect the ecosystem,” Tokoro said. “It’s about being responsible consumers.”

Under Tokoro, Kyodo Senpaku is trying to change the negative narrative surrounding whale meat, including engaging with those it once viewed with suspicion.

“Times have changed and we want to be absolutely transparent … that includes talking openly with the international media,” a company spokesperson, Konomu Kubo, told the Guardian, which declined offers of food and drink at the event.

Japan’s whaling industry has failed to persuade domestic consumers to make whale meat a regular part of their diet. Although it was a staple source of protein during food shortages after the second world war, consumption declined from the 1970s as pork, chicken and beef became more affordable.

According to the agriculture, forestry and fisheries ministry, Japanese consumers ate 233,000 tonnes of whale meat in 1962, eclipsing the figures for beef (157,000) and chicken (155,000).

Masa, the event’s emcee, asked the participants – some of whom were eating the dish for the first time – to “keep an open mind”. As staff brought out plates of deep-fried kushiage with a dipping sauce, he spoke glowingly of whale meat’s nutritional benefits.

“It’s lower in calories and higher in protein than chicken,” Masa said, while acknowledging that there was a resistance to eating “unusual” foods in countries where they were not a part of the regular diet.

The event – the first of its kind – was part of an unprecedented public relations campaign by the whaling industry, four years after the country’s whalers left the Southern Ocean to focus on hunting cetaceans in coastal waters, where Kyodo Senpaku catches 25 sei whales and 187 Bryde’s whales a year.

For decades, Japan’s “scientific” whaling programme was synonymous with confrontations with activists on the high seas, rancorous meetings of the industry’s governing body the International Whaling Commission [IWC], and criticism from Australia and other anti-whaling nations.

Now, though, whale meat is being touted as a tourist attraction, with suppliers and restaurants working in tandem with the Japan Travel Bureau to win over skeptical visitors in anticipation of a sharp rise in overseas visitors after the lifting of Covid-19 travel restrictions.

Earlier this year, Kyodo Senpaku caused anger among animal rights campaigners when it started selling whale meat from vending machines in an effort to boost consumption, with as many as 100 sites planned over the next five years.

The Whale and Dolphin Conservation group described the venture as a “chilling marketing move” designed to “protect a failing industry” that received more than 5bn yen in subsidies from the Japanese government in 2020.

after newsletter promotion

“Past efforts to increase consumption have included putting the meat into school lunches, promotion of whale meat recipes and the creation of a website to showcase where to dine out on the meat. But lack of demand has meant that it ends up in dog food,” the group said.

As he studied the second course – a kaiseki-style selection that included cheek meat in sake lees and tail fin in plum sauce – Amine Habes, a French YouTuber, conceded that not all of his compatriots could stomach the thought of eating whale meat.

“It’s part of Japanese culture, so I understand why it’s eaten here, and personally I respect that and want to try it. But it’s controversial in France. Not everyone is open-minded about it.”

A plate of sashimi – slivers of white and red meat taken from the lower jaw and tail – arrived with instructions from the head chef to wait until it had melted slightly before eating it with soy sauce and grated ginger. “It tasted a little like raw beef,” said Sasha, a Russian influencer.

Tokoro blamed low domestic demand on the controversy surrounding Japan’s now-abandoned expeditions to the Antarctic.

“You don’t find whale meat in many Japanese supermarkets because they came under a lot of pressure from powerful anti-whaling campaigners,” he said. “Now those groups aren’t as active … so we’re trying to change perceptions of whale meat and get more supermarkets to sell it.”

In 2014, the international court of justice ordered a halt to the expeditions after concluding the hunts were not, as Japan had claimed, conducted for scientific research. Five years later, Japan pulled out of the IWC and announced it would end the Antarctic hunts, but resume commercial whaling in its coastal waters.

Now, Japanese whalers are permitted to catch around 200 whales in the country’s exclusive economic zone, although some concede that they are struggling to survive, partly because of a lack of demand among Japanese consumers, who prefer to get their protein elsewhere.

Pimprapa Uematsu, a blogger and YouTuber from Thailand, said she would encourage her followers to try whale meat and have a “special experience” during their visit to Japan. “We also eat things in Thailand that other people don’t eat … you have to be open-minded.”

As they prepared to leave, the diners, armed with gift bags of jerky, canned whale meat and vitamin supplements, wondered how they would describe their culinary adventure online.

“It’s tricky … whatever your opinion you have to share it with your audience, and if what you say is misconstrued it can damage your image as an influencer,” said Mehdi Fliss, a travel blogger from France.

“I’m trying to be objective and want to tell my followers that they should see the issue through other people’s eyes. As long as I deal with the facts, I think it will be OK. But I’m definitely prepared for some negative feedback.”

More Stories

Exploring the “Otaku Island” of Enoshima

Japan eases travel with eVisas

Should you visit Japan or South Korea?